My phone is a box of infinite distractions, a small rectangular portal to endless audiovisual stimulation. I haven’t been bored—not once—since I was a teen with a flip phone and a texting plan. It does math for me, it’s a research tool, it tells me the news, it keeps me in contact with friends that live in other cities and states, and it entertains me when I’m waiting in line or sitting on the toilet.

I hate it.

I’ve spent the last five years of my life trying to unlearn those habits: weaning myself off time-wasting mobile games, checking the news once or twice a day instead of every hour, deleting social media accounts…allowing myself to sit quietly and observe nature when I’m outside, or simply do nothing when I have down time indoors. Sometimes, it turns out, boredom can be a source of inspiration. People used to resort to all kinds of mental activities to keep themselves occupied before the siren song of the phone in their pocket had been composed. Some of history’s best ideas were probably born out of desperate attempts to stave off soul-crushing boredom.

I want to be present in the present. I don’t want to be checking my notifications during family dinners with my wife and young children. I want to force myself to grapple with ideas when writer’s block strikes. I don’t want to instinctively pick up my phone after I finish a paragraph or pause to consider the next story beat. I want to know things. I don’t want to google them. I want to make time to meet my friends and family face to face. I don’t want to Facetime them.

I also want to employ technologies that encourage human health and wellbeing. I don’t want to have anything to do with electronics that are built by underpaid factory workers in unsafe conditions, from minerals mined by child slaves. That’s right: this is an essay about slavery in the global supply chain, and how every green/smart/future technology you love is only possible through exploitation on a scale never before seen in human history. I’m here to make you feel guilty about your smartphone. You’ve been ambushed, and it’s too late for you to click away; you can try, but you’re going to be thinking about those child slaves for at least the next few minutes either way.

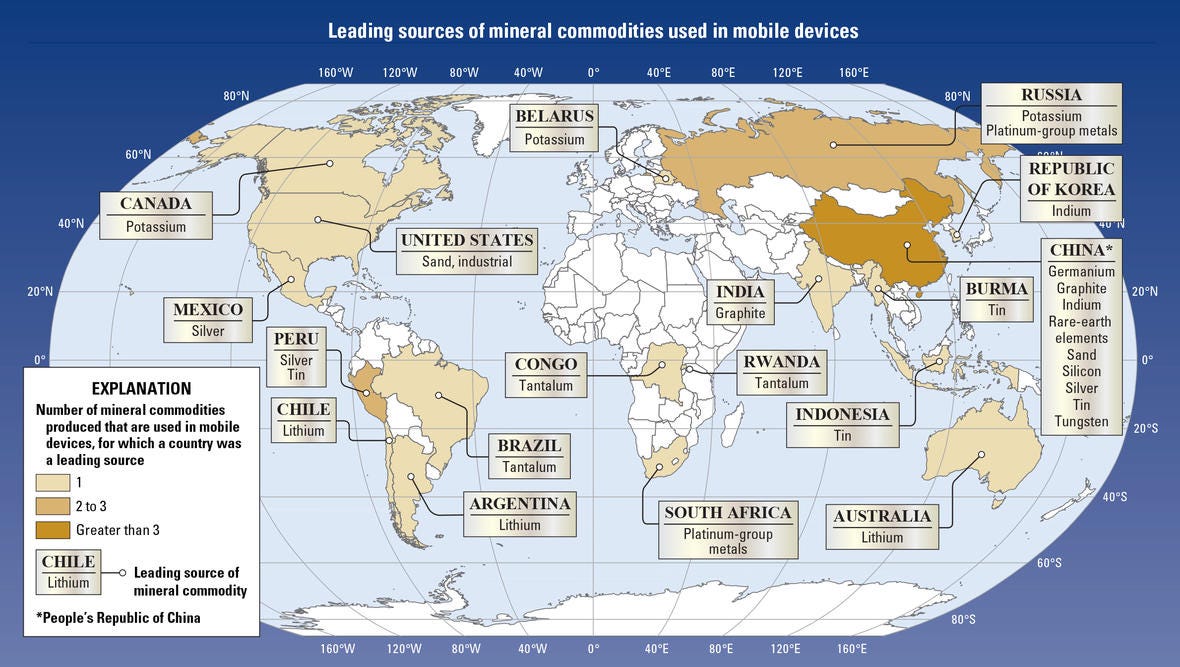

I kid. I’m writing this on a laptop which is made from the same lithium, cobalt, silver, gold etc. as the phone lying next to it on my desk, and feeling making people feel guilty or hypocritical doesn’t help those slaves. Drawing attention to their exploitation can, in principle, but unless enough people make their voices heard and pressure their representatives to hold tech companies like Apple and Microsoft accountable for the deplorable conditions in their supply chains, nothing will change.

Even then, technology has grown into an insatiable beast, consuming billions of metric tons of mineral resources each year, and that demand is only expected to increase as countries transition to low-emission energy sources. If we collectively have to make a choice between human rights and electric vehicles, it’s pretty clear which way things will break, especially when the violations are happening far away across the oceans.

We need to have some difficult conversations, as a society, about what we value and how those values shape the future. Sure, smartphones are sleek little toys, distracting us from our boring office jobs and giving us little Candy Crush dopamine hits on demand, and it’s convenient to be able to speak to people over long distances or look up information without spending hours in a library or navigate with GPS or play any song ever written on demand or watch cats and puppies sneezing on YouTube. But is it worth the cost in human suffering? Is it worth the price of our attention spans? Is it worth handing over decisions of free speech and censorship to a tiny group of unelected technologists, or whatever billionaire happens to get a wild hair and buy their platform?

I hate my smartphone because I can’t give it up—not entirely. I like being able to reach people, and be reachable by people. I like being able to listen to music and podcasts in the car, or watch educational videos on math and science without sitting in front of my old desktop PC. My day job requires two-factor authentication, and the software my employer uses doesn’t allow much flexibility: smartphones are pretty much required. Perhaps, in the distant future, we’ll make better use of our planet’s finite resources and we’ll all carry smaller, less mineral-intensive devices that demand less of our attention. We’ll have to learn to demand less of them as well, but maybe by then we’ll have a better idea, as a society and individuals, of what exactly it is we want—and need—from our technology.