The hour is later than you think.

Humans are problem solvers: we Identify problems and we come up with solutions to them. It takes creativity, hard work, and a lot of trial and error. History is littered with failures—anywhere from 50 to 150 human civilizations predate ours, depending on which anthropologist you ask—but the grand tradition of European Colonialism tends to count them as mere stepping stones towards our current state. More realistically, they can be thought of as prior attempts at large-scale human organization, isolated from each other and from our current global civilization geographically as well as temporally. Though the reasons they failed seemed myriad, there’s a single, insidious dream-killer that played a role in all of them.

Brace yourselves: it’s time to talk math.

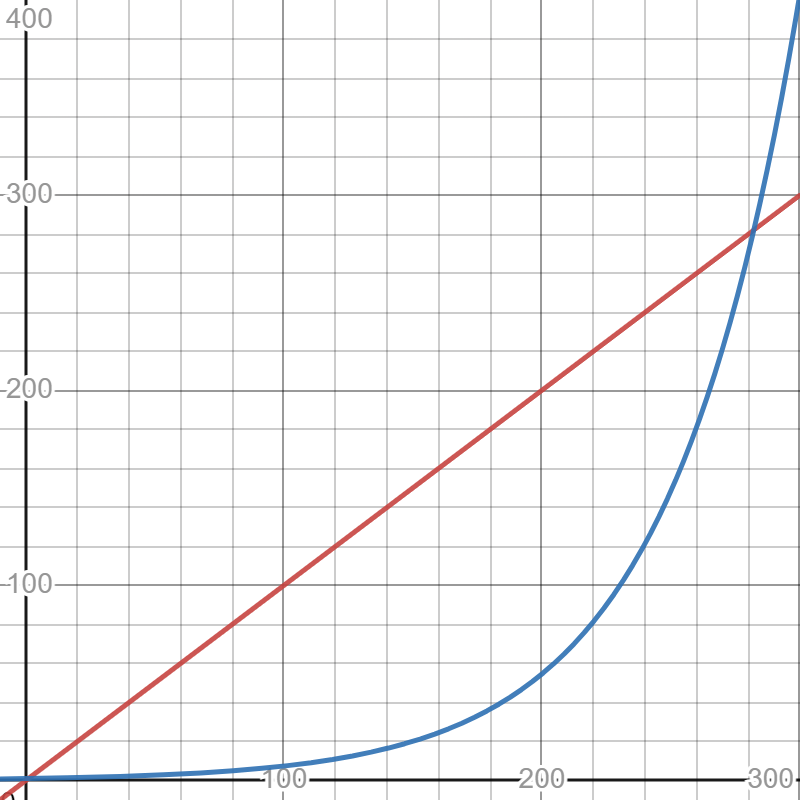

Our ancestors evolved on the savannah, where concerns beyond the day-to-day didn’t exist. If you caught enough prey (or foraged enough edible plants) to feed yourself and your family for the day, avoided being killed by predators, and had a warm place to sleep for the night, life was good. If you observed changes in your environment, such as shifts in the migration patterns of your prey species or changes in the levels of water resources, they were linear: a particular increment of time always produced the same increment of change. If the river levels dropped by a handspan every year, you could read the writing on the wall and begin searching for a new home before it was too late. If, on the other hand, the decrease in water level grew exponentially, then you might not notice for a few years, and even then think the change too slight to be of concern. You might think it a fluke when the year came that the river was half the depth it was the previous and decide to ride it out. The next year, it would be completely dried up. Fortunately for our ancestors, these kinds of exponential changes were rare in their world. Unfortunately for us, they’re everywhere now.

The hour is later than you think.

There are a number of apocryphal stories told, of chessboards and grains of rice, of lilies and ponds, potentially dating back hundreds of years, that illustrate humanity’s difficulties with exponential growth. It’s something we can understand (quite easily, in fact) but it’s not something that comes to anyone naturally, because it’s not something our ancient ancestors had to deal with. We have linear brains, and all the world’s problems today are nonlinear. If we use Earth’s nonrenewable resources at a rate that grows 2% per year (roughly the growth rate of energy demand), then when half of those resources are gone, only 35 years remain until they’re all gone. Every doubling represents an increase equal to all consumption that came before it. Linear growth is simple and easy to understand, but exponential growth is insidious: it poses as slow linear growth for a long time, and by the time it’s obvious what’s happening it’s too late. In one more day, the lilies choke the pond. On the next square of the chessboard, there are more grains of rice than could be grown in 1000 years.

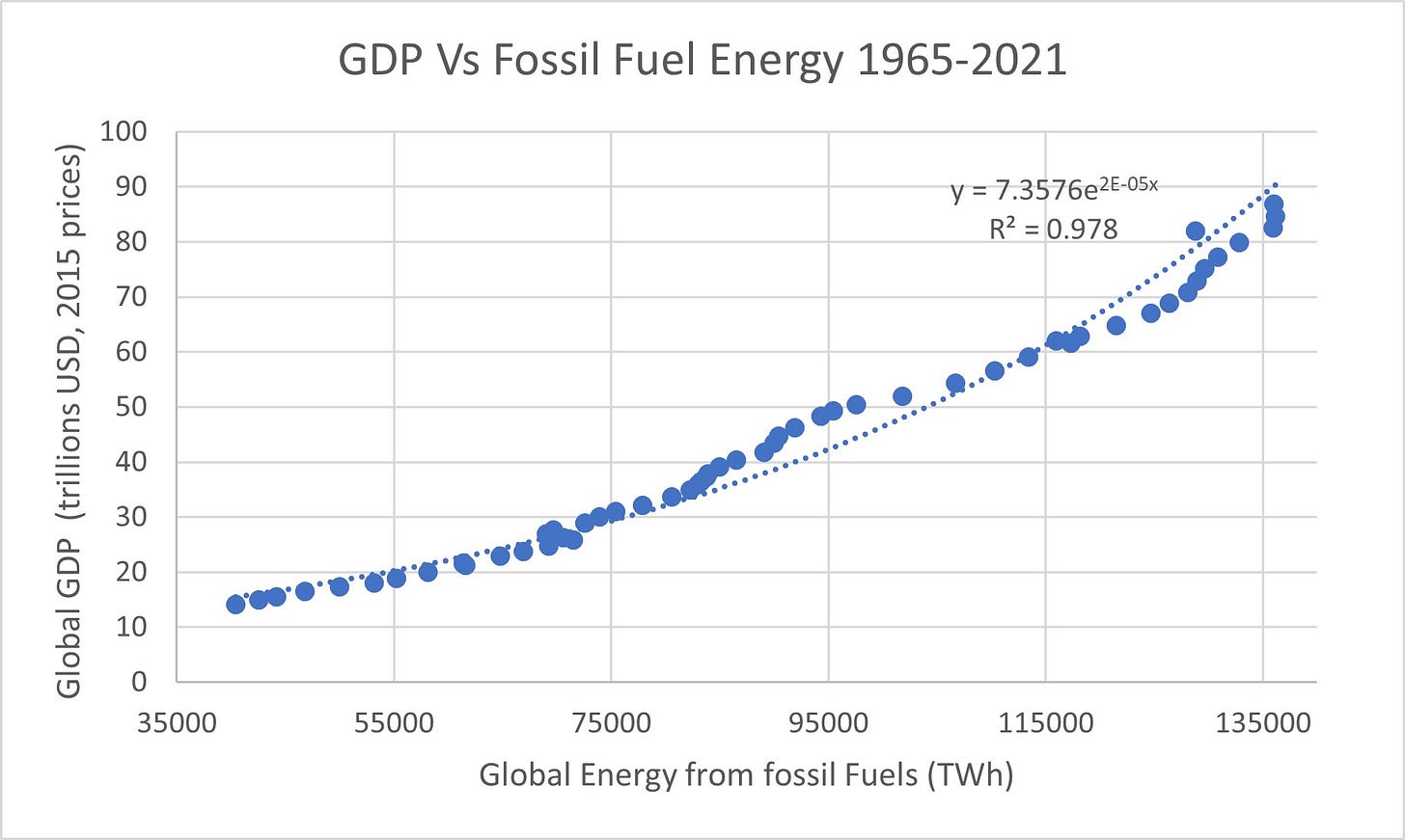

Capitalism requires exponential growth: When economies falter from 3-to-5% growth, devastating recessions result, which hit the poorest segments of the population the hardest. What’s more, economic growth correlates strongly with fossil fuel use, as can be seen in the graph below:

Even strong correlation doesn’t prove causation, but it’s quite hard to imagine a better explanation for what we observe, and the mechanism makes sense: GDP is a measure of the value goods and services produced, and producing anything requires energy. The more energy you use, the more you can make and do, and the energy content of a single barrel of oil is equal to anywhere from 4-10 years of a single adult’s labor. Without this massive infusion of cheap energy, we could never have built the technological world we now take for granted, nor amassed the wealth characteristic of ‘developed’ (oil-exploiting) nations.

I would go so far as you say that the dollar (or any fiat currency from a post-industrial nation) is a certificate of energy use; if you can take a pile of money and ‘invest’ it, and expect to get a 4% return every year, your society had better keep increasing its energy use or you won’t realize those gains. No matter how we get our energy—be it wind, solar, geothermal, natural gas, coal, oil, or nuclear—we cannot keep increasing our use at the same 2% yearly rate we have been since the 1960’s forever: 2600 years from now, demand would exceed the total yearly output of the sun. This means that even if we managed to build a perfect Dyson sphere around our sun, it would fail to sustain our ever-growing demand in fairly short-order—remember, we’ve been a species for around 300000 years, so even 3000 years is just 1% of our history. By the year 6000, we’d use more energy than is output by every star in the milky way combined.

These examples are, of course, ridiculously unrealistic, but they serve to illustrate the point that so many fail to grasp: exponential growth is unsustainable. Period. There’s no wiggle room here, no loopholes, and no amount of human ingenuity will change that. Infinite exponential growth is impossible in an infinite universe, let alone on a finite planet. It has to stop one day, and I suppose that will be the day most people ask ‘what now?’

The hour is later than you think: growing energy demand is but one of many exponential problems facing global human society which intertwine in a complex meta-crisis: a crisis of crises. It would be bold to claim that they are all a direct consequence of inherited linear thinking, but that ancient virtue-turned-vice has a hand in all of them. It remains to be seen if we can kick the habit in time.